Potential new targets for Alzheimer’s Disease

October 30th, 2025 By John Widen

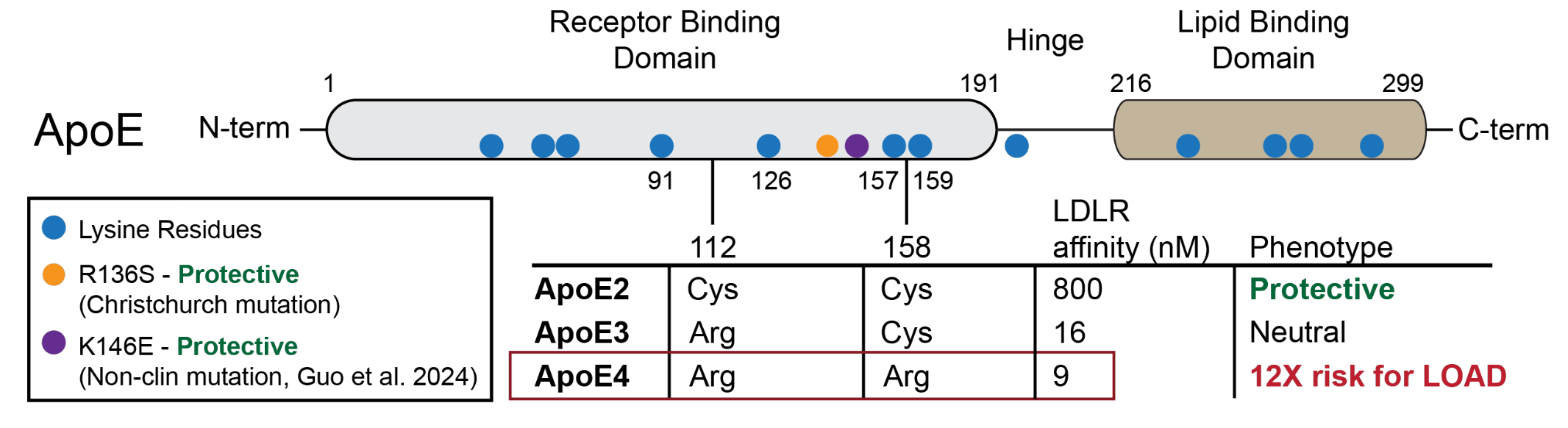

Despite knowing that ApoE4 is the highest genetic risk factor for late-onset

Alzheimer’s Disease (LOAD) for several decades now, the exact mechanism remains elusive.

The APOE4 allele only differs from APOE2&3 by two amino acids (Fig.1).

APOE2 is protective against LOAD compared to APOE3&4 but increases risk for hypercholesteremia.

On the other hand, heterozygous and homozygous carriers of APOE4 have a

3 to 4-fold and 12-fold

increased risk of getting LOAD compared to APOE3 carriers. A rare APOE3 mutation at R136S, referred

to as the Christchurch mutation, delays

the onset of familial Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) by 20 to 30 years.

This mutation on ApoE4 also

confers resistance to AD phenotypes in preclinical models. Furthermore,

Guo et al. (Denali Therapeutics) demonstrated that a non-clinical mutation K146E rescues AD

phenotypes in cell-based and in vivo models of AD. There is a very strong genetic rationale for

targeting ApoE4 to treat LOAD, but the question is what part of ApoE4 biology

is relevant to these phenotypes?

The importance of APOE4 has been (I think) overshadowed by Abeta plaques and Tau aggregates.

This is likely because these proteins can easily be observed in high amounts in the brains

of AD patients. These were the observations made when it was first reported back in 1907.

The problem is that ABeta and Tau levels are not sufficient to diagnose LOAD. Healthy, older inviduals can have the same levels of

Abeta and Tau as patients diagnosed with AD

but do not show cognitive decline.

There have been many failures in the clinic

aimed at reducing or reversing cognitive decline in AD patients.

The majority of these clinical failures involve targeting the production of ABeta including BACE

and gamma-secretase inhibitors, which are involved in processing of Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP).

These failures also include antibodies that bind and clear ABeta plaques through activation of the

immune system. These antibodies have demonstrated that they indeed

clear ABeta plaques in the brain

but do not rescue the cognitive decline in humans. Roche is on a third generation ABeta antibody,

Trontinemab, that includes a recognition domain for transferrin receptor (TfR), which actively

transports the antibody into the brain thereby increasing concentrations.

One big issue with the ABeta antibodies besides the fact that they

reduce plaques in brain but do not rescue cognitive decline is that they

also cause brain swelling referred to as ARIA (Amyloid-related Imaging Abnormalities).

These adverse events can (and has) led to the death of patients. APOE4 carriers are at

increased risk for

ARIA during treatment with ABeta antibodies but why is not understood.

The third-generation antibody, Trontinemab, caused three adverse ARIA events and

one death

out of 143 patients during the phase 1 clinical trial that was reported this summer (2025). Granted the exclusion

criteria and improvements in administering the drug seems to be lowering the frequency and severity of ARIA.

Time will tell if Trontinemab can slow cognitive decline in patients and the benefit of the

drug outweighs the risk of adverse events.

After decades of clinical failures to treat AD, scientists and (hopefully)

funding are looking beyond ABeta and Tau for therapeutic targets. I might be bias,

but I think there has been an increased interest in exploring other pathways and proteins

involved in AD over the past decade and even more so in the past few years.

This brings me to a new

Biorxiv preprint from the Tsai lab at MIT.

This paper uses a genome-wide CRISPR screen in homozygous APOE4 oligodendrocytes

derived from iPSCs (Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells) to identify genes involved in lipid storage.

Lipid and cholesterol storage and trafficking is dysregulated in AD as well as other neurodegenerative diseases,

but many aspects of these mechanisms are unknown.

After infection with guide RNAs,

the cells were sorted for high and low lipid burden using BODIPY staining.

Cells with the top and bottom 15% fluorescent signal were sequenced to identify

enriched guide RNAs in both populations. Identification of genes in the low lipid

cells would identify genes where inhibition could lower lipid burden. Genes identified in

cells with high lipid burden would correspond to genes that suppress lipid formation.

The screen identified a vesicular protein VAMP5, phospholipid

metabolism enzymes (PLA2G4C, AGPAT2, PNPLA6, and PNPLA7), and lipid receptors

such as LRP2 and VLDRL in the low lipid burden cells. These genes have previously been

reported to be involved in lipid droplet formation. More intriguing is that the screen identified

two negative regulators of the Wnt signaling pathway including DKK1 (Dickkopf-related protein 1) and

NKD1 (Naked cuticle 1). There are 336 other genes that were enriched in the low lipid burden cell population.

The preprint did not include the supplemental tables referenced in the texts, but I emailed the corresponding author and she

graciously shared the tables with me. You can download this information here since it is

referenced in the text as public information. I had a cursory look through the table and nothing has stood out to me other than the Wnt regulators,

but maybe I'll follow up after a more thorough analysis.

The genes identified in high lipid burden oligodendrocytes also include

lipid regulatory enzymes. Additionally, TP53, lipid sensor STARD10, and two other

Wnt signaling genes were identified. Interestingly, a negative regulator of Wnt signaling,

APC2 (adenomatous polyposis coli 2), was identified in high lipid burden cells as well.

This is a weird result as you would expect Wnt signaling suppressors to be identified in the

low lipid burden cell population. But biology is complicated and maybe there is something interesting to follow up on in this result.

Two Wnt signaling proteins responsible for activation were

identified in the screen including FZD10 (Frizzled 10) and WNT16. The authors do not provide a

potential reason why APC2 would be identified in the high lipid burden cells.

There are an additional 401 genes that were identified as hits in high lipid cells and is provided in the

download mentioned above.

An interesting result from the screen is that APOE was identified in the high

lipid burden cell population. This makes sense in a cell-based experiment as APOE is

responsible for trafficking lipids out of cells. However, in a biological context knockout

of APOE in AD mouse models reduces lipid burden and cognitive decline. ApoE is largely produced

in astrocytes, not oligodendrocytes. Perhaps in more complex systems oligodendrocytes do not rely

on their own ApoE synthesis for lipid removal. This result might be confounded by the fact

that these cells are alone in 2D culture.

The rest of the publication homes in on the Wnt signaling pathway.

The authors demonstrate that Wnt signaling is decreased in APOE4 vs 3 oligodendrocytes

using ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin-sequencing), which

identifies accessible portions of a genome (i.e. genes that are actively being transcribed).

These findings were compared to a dataset derived from a postmortem human dataset to

show that Wnt signaling genes are also less accessible in humans with APOE4 compared to APOE3.

To demonstrate that pharmacological intervention of Wnt signaling can rescue

lipid burden in cells and in vivo, the authors target GSK3Beta (Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta).

Weirdly enough, this protein is not on the list from the original CRISPR KO screen.

This serine/threonine kinase was first identified in the 1980s as a regulator of glycogen synthase as

the name would suggest. Since then, GSK3Beta has been found to be a cornerstone of many diseases such

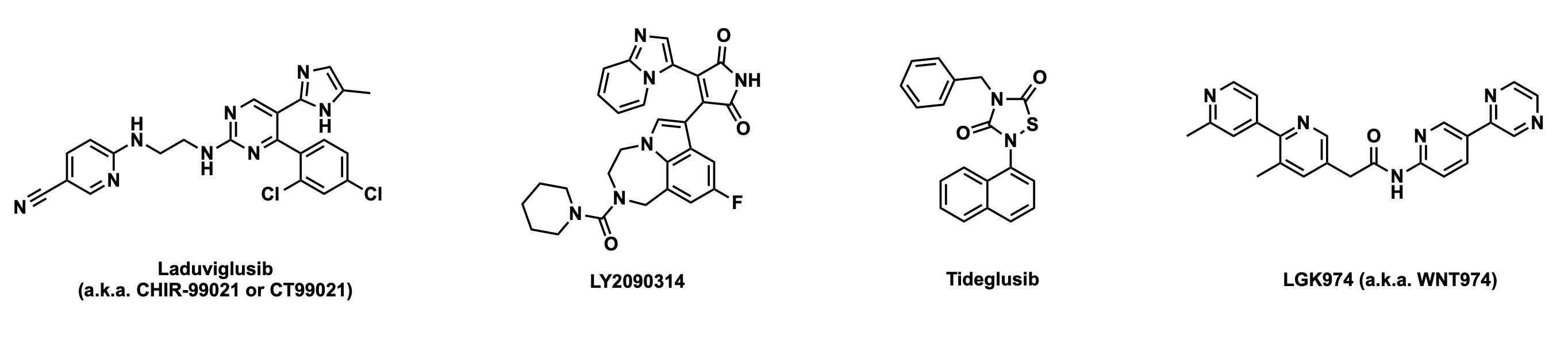

as diabetes, cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and psychiatric disorders. The group uses an ATP-competitive

small molecule inhibitor of GSK3alpha/Beta, Laduviglusib (a.k.a. CHIR-99021 or CT99021).

The structure is shown in Fig. 2. From my perspective, this is the weakest part of the

preprint because GSK3Beta is a cellular pathway hub and interacts with many proteins.

Inhibition of GSK3Beta would affect other pathways besides Wnt including NF-kappaB, STAT3,

and mTOR. GSK3Beta is also regulated by AKT and PI3K. Therefore, any readouts after inhibition

of GSK3Beta cannot be solely attributed to Wnt signaling.

I’ll ignore that the preprint does not demonstrate that Laduviglusib is brain penetrant.

Although there is one report demonstrating Laduviglusib competes with a brain penetrant radioisotope

ligand at low concentrations, the brain penetrance has not been disclosed publicly.

There is also the PK to consider. It is not clear how much the dose administered inhibits GSK3Beta or for how long.

The group also reports in the preprint that Laduviglusib does not reduce the pTau levels in

the mice brains versus control, which has been demonstrated previously.

To be fair there are not a lot of options when considering an in vivo tool

molecule for Wnt specific modulation. Targeting GSK3Beta might be best and only option.

There has been interest in developing GSK3Beta inhibitors for quite some time but clinical success

remains elusive. Development of GSK3Beta inhibitors has been hampered by the high similarity of the ATP

binding pocket to GSK3alpha and other kinases. Several molecules have failed clinical trials including LY2090314

and Tideglusib (Fig. 2). Tideglusib is a covalent small molecule! The history of developing small molecule inhibitors of GSK3Beta is

complicated but it seems that folks are interested in allosteric modulation. Because GSK3Beta is important to

many cellular pathways, I can see how complete inhibition of the kinase activity could lead to dose limiting toxicities. Maybe as a part two, I will dig into the history

of GSK3Beta inhibitors. Stay tuned!

This and other publications suggest that aberrant Wnt signaling is involved in

neurodegeneration and various cancers. There are plenty of reported

inhibitors and

activators of the

Wnt signaling pathway (more so on the inhibitor side). Inhibitors of Wnt signaling are at the clinical stage that would

presumably have reasonable PK and potency such as an inhibitor of Porcupine (PORCN) like LGK974 (WNT974, NCT02278133). I haven't been able to find

a direct activator of Wnt signaling in clinical trials (excluding GSK3Beta).

Regardless, I enjoy seeing publications that aim to identify new targets and pathways for neurodegenerative disease. These diseases are complicated and still

poorly understood. A lot of that is because there is a lack of small molecule tools to evaluate these pathways in cell-based and animal model experiments.

This study is limited by the available tools to therapeutically validate the proteins identified in the CRISPR screen. Genetically ablating these targets in an animal is an expensive way

to get around this issue and that can take years. Screening new protein targets against small molecules is a good start

on the way to having more tools for interogation of neurodegenerative diseases. I'll stop there, thanks for reading.

The site does not have a comments section yet! Hopefully, very soon! Until then please drop me a line at jwiden@chemjam.com. If you provide comments on my articles I reserve the right to post them on this website as additional commentary. My goal is to have an open discussion!